Flooding From A Blighted Land

The migration of the Irish to Newport in the 1800s.

How the humble potato led to a human exodus of epic proportions from Ireland.

By Jim Dyer

First published in the South Wales Argus October 1986

© Jim Dyer 2012

They crawled through the mud of the Usk's banks, jumped ship, were dumped or swam ashore in their desperation to reach Newport. They were the starving Irish immigrants to whom the grim conditions of the 19th Century Monmouthshire were a haven compared with the famine they fled.

Families wandered

the streets totally destitute.

Records show that in 1801 the population of the town was only just over 1 000. But by 1851 Newport and Pillgwenlly had swollen to nearly 20 000 and was expanding rapidly.

Newport's importance for the coal and steel industries, the canal system linking the rest of Gwent, and not least, the envious position of the river and port for all kinds of imports and exports attracted many new settlers to the town.

They came from all over the country - Scotland, Staffordshire, the West Country and the great mining valleys of South Wales.

But it was the severe conditions of the 19th Century which ensured a permanent place in Newport’s history for the many Irish who flooded over to escape poverty and starvation. Over generations they have settled here being part of the community retaining their national identity customs and games. There is even an Irish Club here!

Many families can trace their roots back to those bad old days in the Emerald Isle and given the terrible circumstances it is no wonder memories die hard.

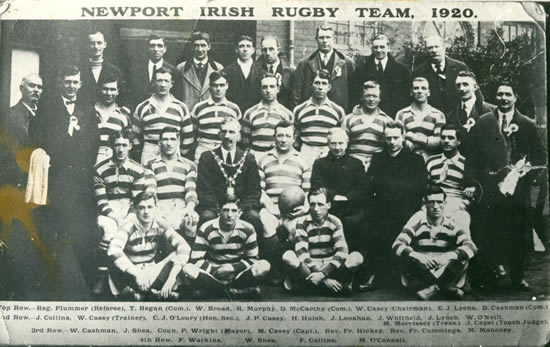

Newport Irish Rugby Team 1920

The Irish Famine

It was the humble potato solarum tuberosum which precipitated the tragedy of the vast emmigration from the country. No other countries were more reliant on the potato than the Irish thence the nickname 'Spud'. In 1846 blight swept the country causing misery and half a million peasants died from starvation. Poverty there horrified many a visitor. The 1841 Census showed that lots lived in appalling conditions, furniture was a luxury and on the west coast it was found many lived in windowless, mud-floored cabins.

The terrible famines of 1846 and 47 caused over one and a half million to flee, entering Britain in three main areas - Liverpool, Glasgow and the Clyde and the South Wales ports.

Cheap deck passages could be got for a few shillings and exports from Cardiff to Cork meant that free passage could be had to provide ballast. South Wales was only a few hours away and many seeking to escape starvation misguidedly thought they would be better-off in Britain even in the workhouse. Captains would often dump them in the mud of the Usk.

Misery

The scene at the river itself must have been horrific. At best a throng of emaciated ragged men women and children would stagger from the holds half dead to make their way through the town to the workhouse on Stow Hill.

The Monmouthshire Merlin in February 1849 records about 200 mainly sick were thrown ashore by an Irish collier, some way down the river, to find their own way to town. The next day 60 crawled from the mud banks to the streets. The steady flow would continue for two to three months. The Merlin of this time is crammed with such heart-breaking stories.

Many were seen begging on the streets without shoes or stockings and there were tragic reports deaths, soup kitchens, hunger and misery. One woman clutching a suckling baby walked the streets bare-footed. They lived squalidly and had few possessions.

The Poor House records indicate that from January to May 1847 12,872 cases were dealt with, including a vast number of Irish who were 'fed and lodged.' By 1849 the population of pillgwenlly alone was 7,000 or so and the Merlin indicates that in one month 1,500 Irish went into the Poor House.

Many Irish landlords encouraged their tenants to leave giving them their passage money and soon the emigration was recognised as a national problem. Municipal authorities were given the power to send Irish paupers but many continued to flock in, wending their way to all parts of the country to find friends or relatives.

Paupers

In 1847 the Mayor of Newport detained a vessel belonging to a Skibbereen grain erchant because it had been used to land paupers. There was much hostility in the town to the transporting of the poor, destitute Irish. Over 60 imported from Skibbereen and Clonkilty died on landing from fever and famine.

Even Chepstow was warned that that an influx of Irish paupers was advancing on the town from South Wales. Irish tramps were common.

In 1849 William Sutton, the Master of Mary. a schooner from Cork, was fined £50 for dumping Irish in the river bank. Others were warned 'All masters bringing Irish paupers here in a similarly illegal manner may expect the same treatment.'

In May of the same year another cargo of starving Irish was thrown ashore from the Catherine. Some died on the journey to Stow Hill. Families and their children were sometimes separated, often with tragic consequences.

In 1849 the Abaelino left for Boston where a large Irish colony was steadily growing. It is likely that a fair few of those early Newport Irish set sail again searching for a better life. To the good of the town many decided to settle here and raise their families, bringing their own style to society.

The 1861 Census shows street upon street of Irish residents - hardly any English (or Welsh) to be found in some areas of Pill and Baneswell. Some of the names can be still found today - Donovan, Murphy, Coade, Kennedy, Mahoney, O'Connell, Ryan etc… and all thanks to that little potato.

Jim Dyer - 28th December 2011

NOTE

First published in South Wales Argus on 23rd October 1986.